This is an article in draft that I found on my Drafts dashboard that I originally (mostly) wrote well over two years ago but never published. Although I did post the photos on Facebook, I never posted them here. This is a strength of blogging that’s difficult to duplicate in social media - finding things from previous years.

—————

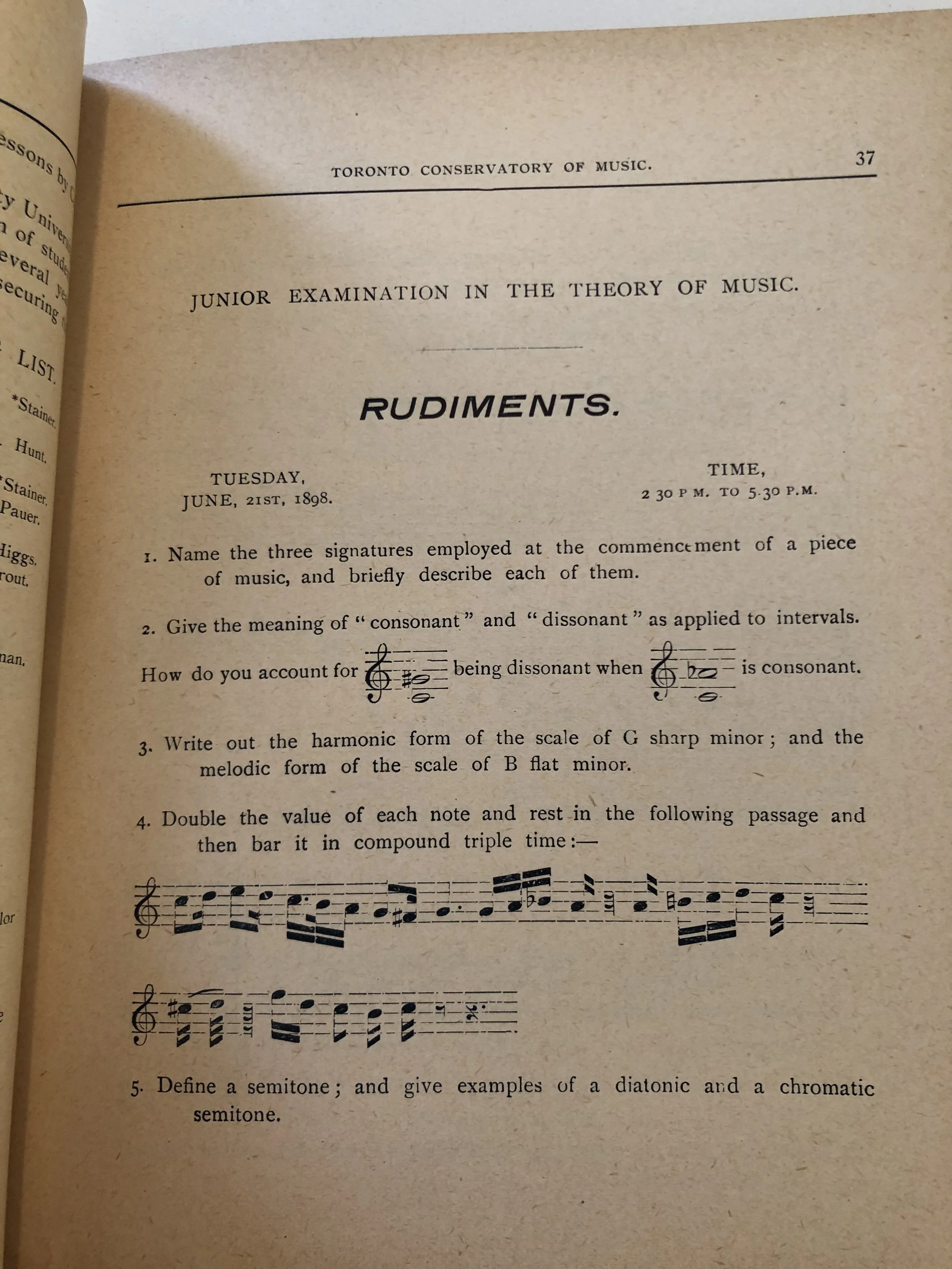

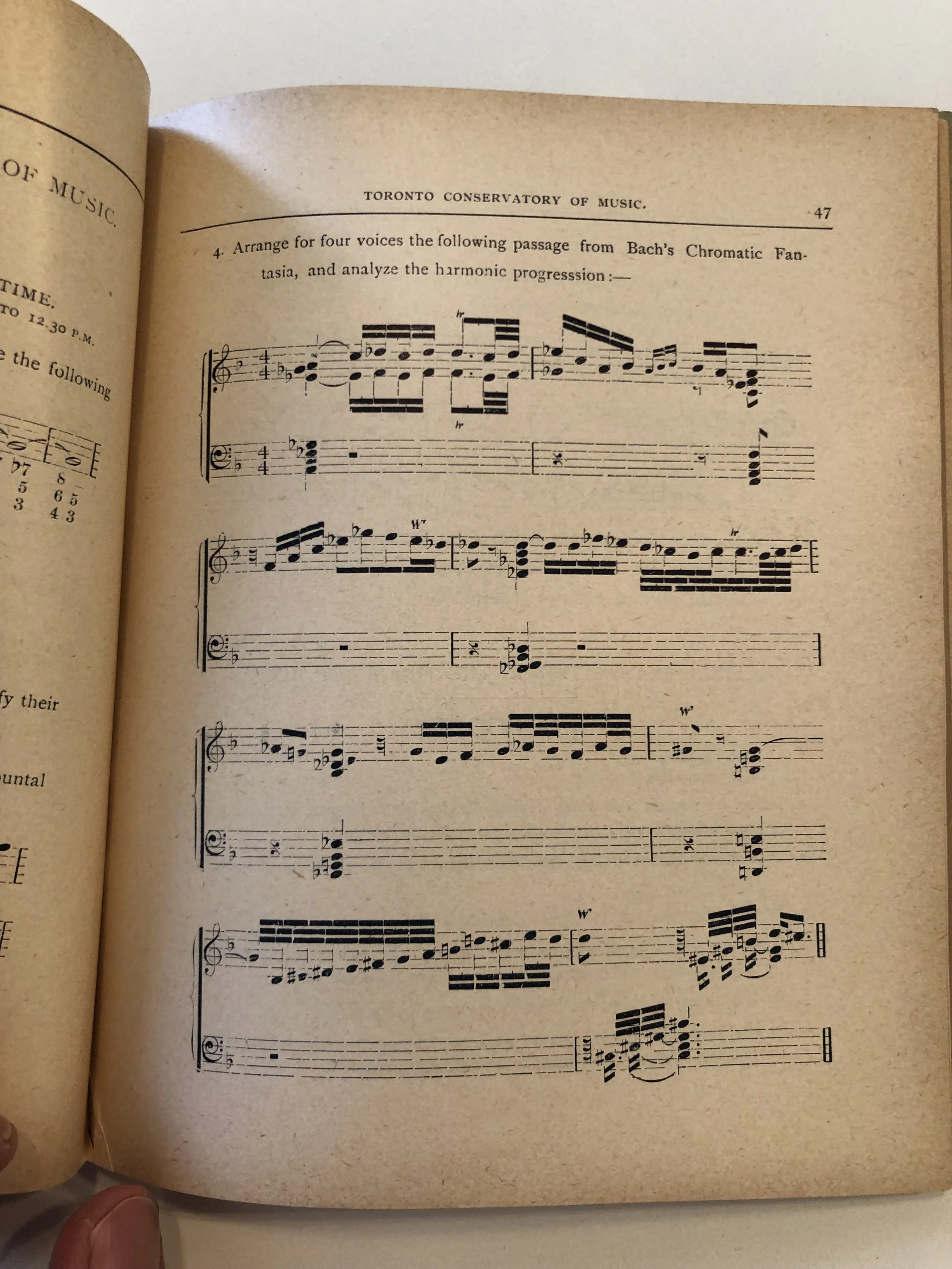

Back in November 2022, Wendy and I met up with The Royal Conservatory’s Chief Examiner Emeritus Tom Green to visit the Toronto Old Paper and Book show. One of my side quests in the last while has been tracking down old Royal Conservatory materials - I’ve got a 1918 Technical Requirements manual as well as syllabi from 1925, 1926, and 1927. These old documents can be hard to come by, so the OPB show was one of the only places where one might find, by chance, one of these relics of Toronto’s musical life of yesteryear.

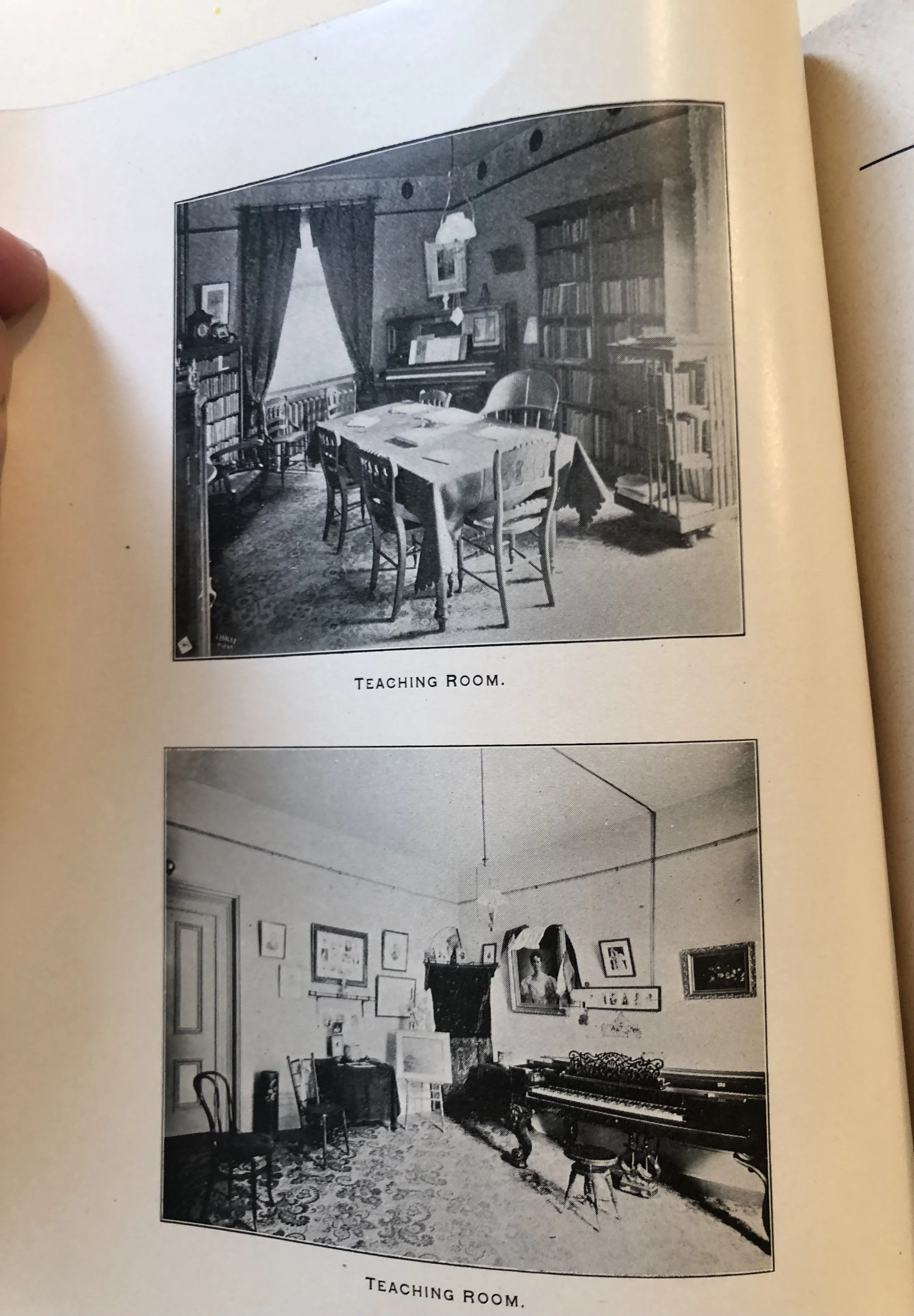

And I hit the jackpot, finding an 1898 annual calendar from the Toronto Conservatory of Music, the former operating name of The Royal Conservatory. This was the annual prospectus given out to the community that showcased photos of the TCM’s new digs at the SW corner of College and University in downtown Toronto (now the site of the Ontario Power Generation building), information about course registration, a listing of faculty and their rates, highlights from the annual meeting, as well as a complete listing of recent graduates.

Here are some interesting things about the old conservatory building, some of which I gleaned from the calendar and some from elsewhere:

The old Toronto Conservatory building was right across the street from the Ward, Toronto’s first multicultural neighborhood. Immigrants from many communities first settled here in Toronto, and the conservatory was a readily accessible cultural institution where they could learn both music and speech arts.

At the corner of University Avenue and College Street, the building was easily accessible via streetcar, and after 1963 by subway - the Queen’s Park TTC station was right by the building.

In the absence of central heating, studios and practice rooms were heated by fireplace.

The Conservatory Music Hall was one of Toronto’s lost musical treasures, and featured an electric Casavant organ.

Private lessons with Edward Fisher were $40 a term, consisting of a term of 10 thirty-minute lessons. With the rate of inflation calculated from 1914, that is now the equivalent of at least $1075.33, or more than $100 per half-hour lesson, over $200 per hour in current dollars allowing for inflation. By way of contrast, lessons with Edith Crittenden would have cost a much more reasonable $21.50 per lesson.

Here’s a question from the June 1898 history exam that I found to be quite challenging for our 21st-century sensibilities:

Write a short life of that great master who was born in Germany last century, and who died in England this century.

Which composer was this? Bear in mind the date of the history exam and leave your answers in the comments.